|

Philippines, 30 Jan 2026 |

Home >> News |

|

||||

|

|

|

|

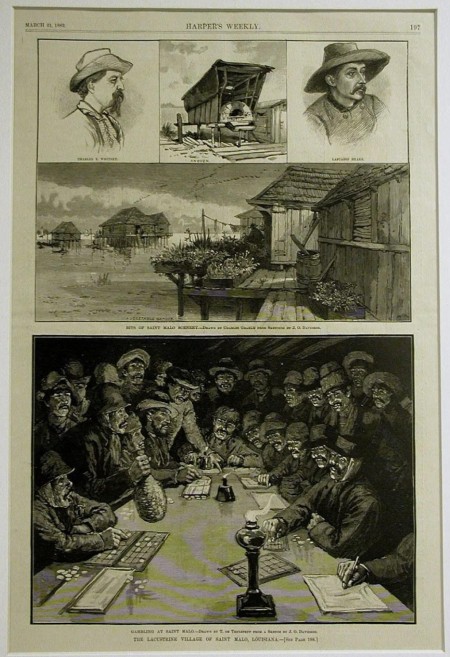

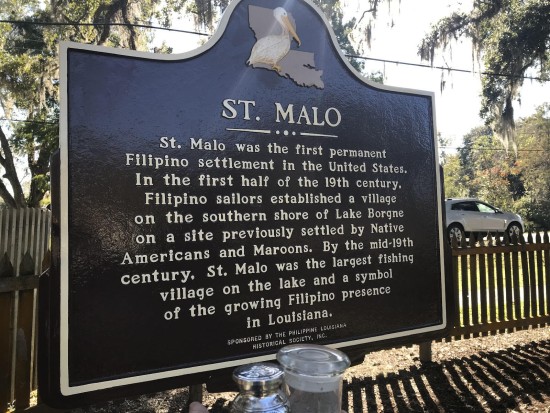

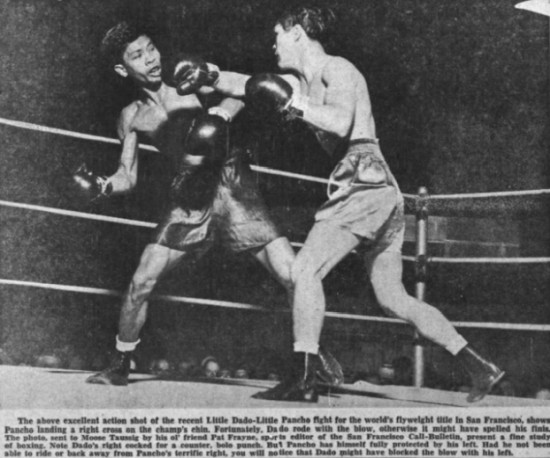

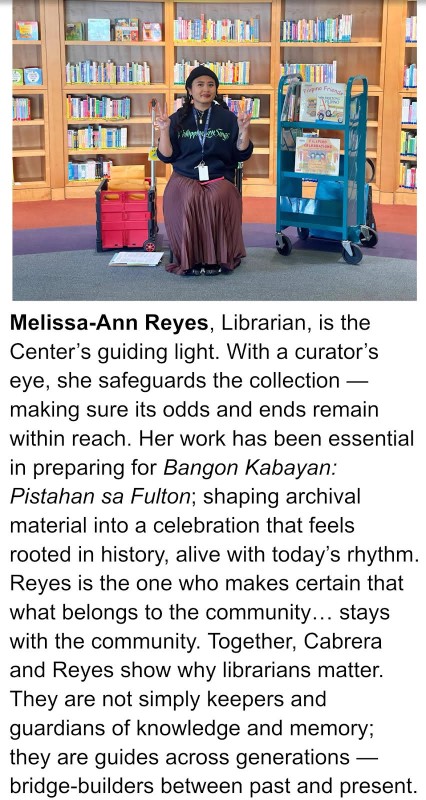

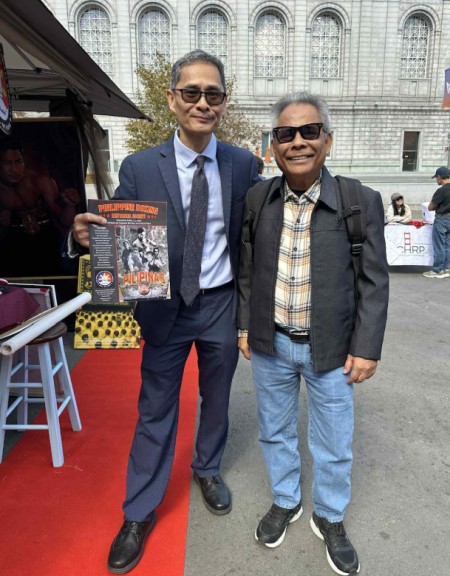

Mabuhay at Salamat: ‘The Thirty’ Filipino Boxers Who Became Giants By Emmanuel Rivera, RRT PhilBoxing.com Mon, 24 Nov 2025  In this Season of Thanksgiving, we humbly offer this tribute and artistic photo rendition, drawn from original photographs, in honor of The Thirty Filipino fistic pioneers whose faces mirror our own story. Roll Call Duarte • Labra • Giner • Villon • Jamito • Cabanela, Sr. • Reyes • Flores Brothers—Francisco, Macario, Ireneo, Elino • Sarmiento • Guilledo • Concepcion • Gan • Moldez • Hill • Bueñaflor • Baguio • Tingson • Dano • Yaba • Milling • Tenorio • Posadas • Opao • Fernandez • Garcia • Zapanta • Rogers Behind every name is a heartbeat that has endured for more than a century — a Filipino rhythm, a Pinoy fighting spirit we still carry today. What follows is only a part of their story — and ours — told through the lens of boxing. It began at Pier 7 in Manila Bay, where Filipino fighters boarded westbound ships with clenched fists, borrowed Sol Levinson gloves, and whatever chance they could grab for a new life. The Philippines shaped them long before the Pacific took them west. They were dreamers, wanderers, factotums, farmhands, soldiers, fighters — Filipino boys who learned to box anywhere a ring could be set up or imagined. They climbed the undercard and eventually fought alongside Yankee GI’s at the unofficial and exclusive fight den called Olympic Club on Calle San Geronimo in Quiapo. They fought under open skies at Palomar Park in Tondo, and inside the cauldron called Olympic Stadium along Avenida Rizal and Calle Doroteo Jose — where crowds roared to the high heavens.  They left Manila not as champions but as young fighters stepping into a future none of them could fully envision. They boarded military vessels built more for war than anything else. Many slept beside crates, ammunition and cargo. Their names weren’t known at the time, but their will and resolve pushed them forward. Their journey crossed the Pacific and brought them to San Francisco — a place wide enough for their stories to unfold. No banners, no headlines, no promises awaited…Just the idea that if they kept moving, they might land on streets paved with gold.  Sol Levinson gloves at the Embarcadero (Ferry Building and Clock Tower, San Francisco, October 2025) The Bay met them with thick fog, bone-chilling wind, and a stiff challenge. By the time they caught sight of the Ferry Building clock tower and stepped onto the piers along the Embarcadero, something in them stirred. They had reached what the conquering Yanks called “God’s Country.” Hunger and hardship— not to mention pestilence, subjugation, typhoons, floods, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions— shaped them and gave them the necessary credentials and fortitude to succeed in a foreign land.  The City of San Francisco was the place where the Filipino boxers’ rise in America began. On Market Street, they settled into the American story as immigrants who became folk heroes, in the stretch south of Market Street that would one day be known as Little Manila — the earliest Filipino enclave to rise in a major American city.  Photo: The lacustrine village of Saint Malo, Louisiana: Bits of Saint Malo scenery (Drawn by Charles Graham from sketches by J.O. Davidson). Saint Malo, first described by Lafcadio Hearn for Harper’s Weekly (March 31, 1883) Long before that, Filipino sailors who plied the Acapulco–Manila galleon trade for Spain decided to stay in New Orleans and built the lacustrine village of St. Malo on the marshes of Lake Borgne in Louisiana — a quiet settlement shaped by wind on the water, shifting reeds, and boats knocking gently against their moorings.  Formed in the early 1800s, it stands as the first permanent Filipino community in the United States, a reminder that our story here began in the stillness of the water before it ever reached the noise and brightness of the big city.  Photo: (L) Bill Graham Civic Auditorium • (R) San Francisco City Hall Filipino fighters walked into gyms and boxed at halls where nothing came easy. From the 1910s through the 1940s, they fought in clubs up and down the West Coast — including the Grand Olympic Auditorium in Los Angeles — where crowds moved from doubt…to surprise…to respect.  Photo: Dreamland Rink–Auditorium (Then and Now) Eddie Duarte — the first professional boxer from the Philippines — fought at Dreamland Rink and paved the way for the likes of Macario Villon, Speedy Dado, Small Montana, Little Pancho and Little Dado. Here in the Bay, the story of Francisco Tingson Guilledo leaned toward both triumph and tragedy. Known as Pancho Villa, he fought his last bout at the old Oaks Ball Park in Emeryville on July 4, 1925. Most ringside observers — and nearly every newspaperman — had him winning, but the lone judge, referee Bobby Johnson, ruled it differently. Ten days later, in San Francisco — a city sharing the name of the saint he was likely named after — Francisco Tingson Guilledo passed away with the world crown still in his possession. Ceferino Garcia turned the bolo punch into something distinctly his own at Dreamland on Post and Steiner. Ringside writers noted that Ross received the decision and Garcia was denied the win on September 14, 1935.  Photo: Little Dado–Little Pancho world flyweight title fight. Pancho lands a right cross. (Honolulu Star-Advertiser, Jul 1, 1940) The last championship bout here was the Little Dado–Little Pancho draw at the San Francisco Civic Auditorium (now the Bill Graham Civic) on June 17, 1940.  Decades later, Gabriel “Flash” Elorde, Luisito “Lindol” Espinosa, and Emmanuel “Manny” Pacquiao walked the same streets and fought in the Bay Area — carrying the memory of those who came before us. The squared circle kept going, evolving. Boxing reshaped itself, and our Filipino fighters stayed in the mix— in California to New York and somewhere in between. Size, as the saying goes, does not matter on the path to greatness. For over a century, the names of The Thirty waited quietly in archives, trunks, and scrapbooks… fading ink… fragile clippings… until one windy autumn afternoon at the plaza.  Bangon Kabayan — Pistahan sa Fulton became something more than a gathering. On October 11, 2025, at the Fulton Steps in Civic Center, the journey bent back to where many of these paths first touched America. The barrio fiesta honoring Philippine boxing carried the feel of a homecoming — in its own way. People from different walks of life — boxers, martial artists, families, passersby — formed a modest crowd that seemed to move with one steady pulse. For a brief moment in time, San Francisco felt just a little like Manila. This revival happened because a Filipino and American community decided the past deserved light. Librarians, curators, organizers, artists, folk dancers, boxers, martial artists, families, and friends — each lifted a corner of the story until it rose into view.  The gathering at the Fulton Steps in San Francisco would not have been possible without the support of friends, family, and our Filipino and American community. We thank Jaena Rae Cabrera, project manager, and Melissa-Ann Reyes, librarian of the Filipino American Center at the SFPL — whose care and steady vision gave us a chance to share the story of Philippine boxing.  Jaena Rae Cabrera (Photo Courtesy of Andre Canta / Mahalaya. Jaena Rae Cabrera brings a journalist’s curiosity and a librarian’s touch. With degrees from San Francisco State University and Syracuse, she shaped programs that moved history out of the shelves and into the community. She served on national stages too…co-director of the Filipino American International Book Festival; president of APALA. She has a way of making gatherings feel familiar, blending scholarship with celebration.    The LIKHA Pilipino Folk Ensemble carried our traditions through music and dance. Power Struggle and Bayani Art showed how culture grows when people create together.  To our friends — old and new — at the Philippine Boxing Historical Society and Hall of Fame…Thanks.  Our Pinoy boxers began their fistic journey in Manila and reached San Francisco — a city that welcomed them, much as it welcomed us, the doers and dreamers like my niece Keana Christine Rivera and her mother, my sister Charina.  We are also thankful to Master Danovis “Dee” Pooler and Kru Mark Tabuso of Evolve Martial Arts, who showed that boxing and footwork grow from rhythm, art, and discipline tied to Filipino Martial Arts.  To the Medida Family— Joan and Ryan and their daughters Athena Ryanne and Hera Joanne— Salamat for your presence.  To Sir Dong Secuya, founder of PhilBoxing.com — Daghang Salamat. We look forward to more stories, and many more rounds, with you in our corner.  A Boxiana Homecoming for The Thirty They were the thunder before the storm, the sound that told the world something was coming. On their shoulders, we continue to rise. They took the steps others hesitated to take and refused to live as footnotes in the story of the fight game. With courage, resourcefulness, and the truth carried in their fists, they lifted the heart and soul of us Filipinos onto the world stage — and in so doing, they became giants. Sila ang kulog bago ang bagyo. Dahil sa kanila, patuloy tayong umaangat. Tinahak nila ang mga landas na inatrasan ng iba, at hindi pumayag na maging pahapyaw na tala sa kasaysayan ng boksing. Sa tapang, talino, at lakas ng kanilang kamao, iniangat nila ang puso at kaluluwa ng Pilipino sa harap ng mundo — at sa gayon, sila ay naging mga higante. Mabuhay at Salamat. Happy Thanksgiving! Sources and Acknowledgements The artistic collage and rendition of Filipino boxing greats were digitally designed and created by ManoyTKO, faithfully using modern tools with reference to archival materials from The Ring Magazine, the Manila Daily Bulletin, the National Archives of the United States, San Francisco newspapers (the SF Examiner, SF Bulletin, and SF Call), the San Francisco History Center at the SFPL, and various vintage trading cards and photographs that have been preserved over time. All other photographs in this article were taken by us, or shared from sources long committed to remembering our past. We make no claims of ownership, only the responsibility of caretakers who wish to share them with reverence. These images— spanning the 1910s to the 1940s— are presented under the United States Fair Use Doctrine for non-commercial, educational, and historical purposes. Click here to view a list of other articles written by Emmanuel Rivera, RRT. |

|

|

PhilBoxing.com has been created to support every aspiring Filipino boxer and the Philippine boxing scene in general. Please send comments to feedback@philboxing.com |

PRIVATE POLICY | LEGAL DISCLAIMER

developed and maintained by dong secuya © 2026 philboxing.com. |